The Wheelset

/Page 1.Day 5

Wheels can transform your bike by improving lateral stiffness, aerodynamics, cornering grip, and comfort. But with more options than ever—buying the best wheels for your budget can drive you insane. If I could do one thing to upgrade my bike—and I was spending my own money (the most valuable kind)—I’d buy hand built wheels from John Drake at Tangent Cycles. If you’re asking “Who…?” allow me to explain.

The 25,000-mile wheelset.

The axis in John Drake’s process of constructing bikes is wheels. For forty years Drake—tinker, philosopher, mathematician—has been studying and building wheels using the latest science, engineering, and innovation, constantly updating the profile, structure, lug, brake, and track. Every aspect of the wheel.

A wheel from John Drake today is the latest iteration of this journey—bringing increased stability, comfort, rolling speed, weight loss, and aerodynamics. Whether with tubular wheels and tires or more user-friendly clinchers, or carbon rims with the smoothest ceramic bearings, or an expanded rim width with an expanded tire volume for a plusher ride and healthier meat on the tarmac, or a wheelset for your all-mountain endeavors—John will improve your bike’s handling, lower the rolling resistance, and offer a smoother ride and a good dose of speed. These are hand built steamrolling hoops that have been documented to have reached 25,000 miles.

“Precision tools are our friends, precision tools sing arias of irrefutable fact, that soar above choruses of subjectivity and slant.”

—Dan Neil, The Wall Street Journal

Right now, Drake, tall with arms like iron and a broad good-looking face, is standing at his workbench, where a transformation is taking place. He’s cutting spokes to length on a Phil Wood Spoke Cutting and Threading Machine. I watch as John hand-cranks the machine and the spoke swivels up and forward on its marvelously engineered multi-axis hinge and finishes with a crack, like the crack of a whip. This machine’s frame assembly—its slide, block, alignment guide, and crank—is as compact and elegant as a scientific theory. This is a $6,000 spoke machine that cuts and rolls factory-quality threads in one jaw-dropping motion (and the jaw-dropping bar is set pretty high around here). This is the tool used by Campagnolo, DT Swiss, Shimano, HED, Wheelsmith, and John Drake of Tangent Cycles.

In Japanese the word kodō means “heartbeat,” the primal source of all rhythm. John’s shop has kodō to the nth degree.

Building bikes is a special world, and tools are the vernacular that helps the constructeur, or mechanic, create it. Walk into John Drake’s Tangent Cycles and tools are easily the first thing you’ll see. Tools from Snap-on, Var, Abbey, Rolf Prima, Phil Wood, and others. Tools that don’t take price into account line the wall above John’s workbench, like custom-fitted leather luggage.

-

This is a shop that is entirely coherent. Self-contained. A tiny civilization all its own. At the moment, John is cutting and making bundles of spokes. One bundle is 276 mm for the nondrive side; another is 273 mm for the drive. There is no music, no talk. John’s all business. The spokes are Sapim CX-Ray and are bladed in shape, with a 2.0 mm diameter at the ends and a width of 2.2 mm and a depth of 0.9 mm in the middle. They are not only some of the lightest spokes made but also some of the strongest—and make for extremely strong wheels.

A granite table with a BMI of 30.

John turns a half left and walks across the shop to a table nearly the size of a VW Polo without the sneakers. It’s a total landscape—bulky, yes, but a complete thoroughbred. Used by frame builders to tune and true and torque frames. It’s a beast with a curb weight of 1,200 pounds. The table is 36 inches wide, 48 inches long, and 10 inches thick and sits on a metal stand that is 33 inches tall with subsurface anchors. It’s a granite surface plate (granite table) with a surface flatness defined and specified as Tool Room Grade = Laboratory Grade AA, as smooth as the bits of glass I found as a kid on the beach at Cape Cod. This is a table that guarantees flatness tolerances that exceed the requirements of its own specifications (you might say the same about the owner). This is the table John Drake uses to check the flatness of his rims—getting everything on one plane—because even an imperceptible twist in a wheel will show up as you’re truing a couple thousandths of taper.

With the sound of an empty galvanized pail set down on stone stairs, John sets a rim on the table. Raising his eyebrows, he bends down and stares at the rim. Pauses. Turns the rim. Pauses. Turns. Pauses—looking for any imperfection, imposing levelness on an irregular world. Finally, under his trained eye, the rim passes muster. Drake grabs the rim, walks back to the workbench, sits down on a Park swivel stool—the perfect destination for hours of handwork—and begins adjusting all the brass nipples so that each is screwed equally far onto its spoke. He’s double-checked his spoking pattern and is bending the spokes by hand so they fit snuggly against the sides of the hub. Next, he takes the wheel and sets it up on his truing stand.

At this point I’d like to clear the room of anyone who is not a huge nerd. Ready?

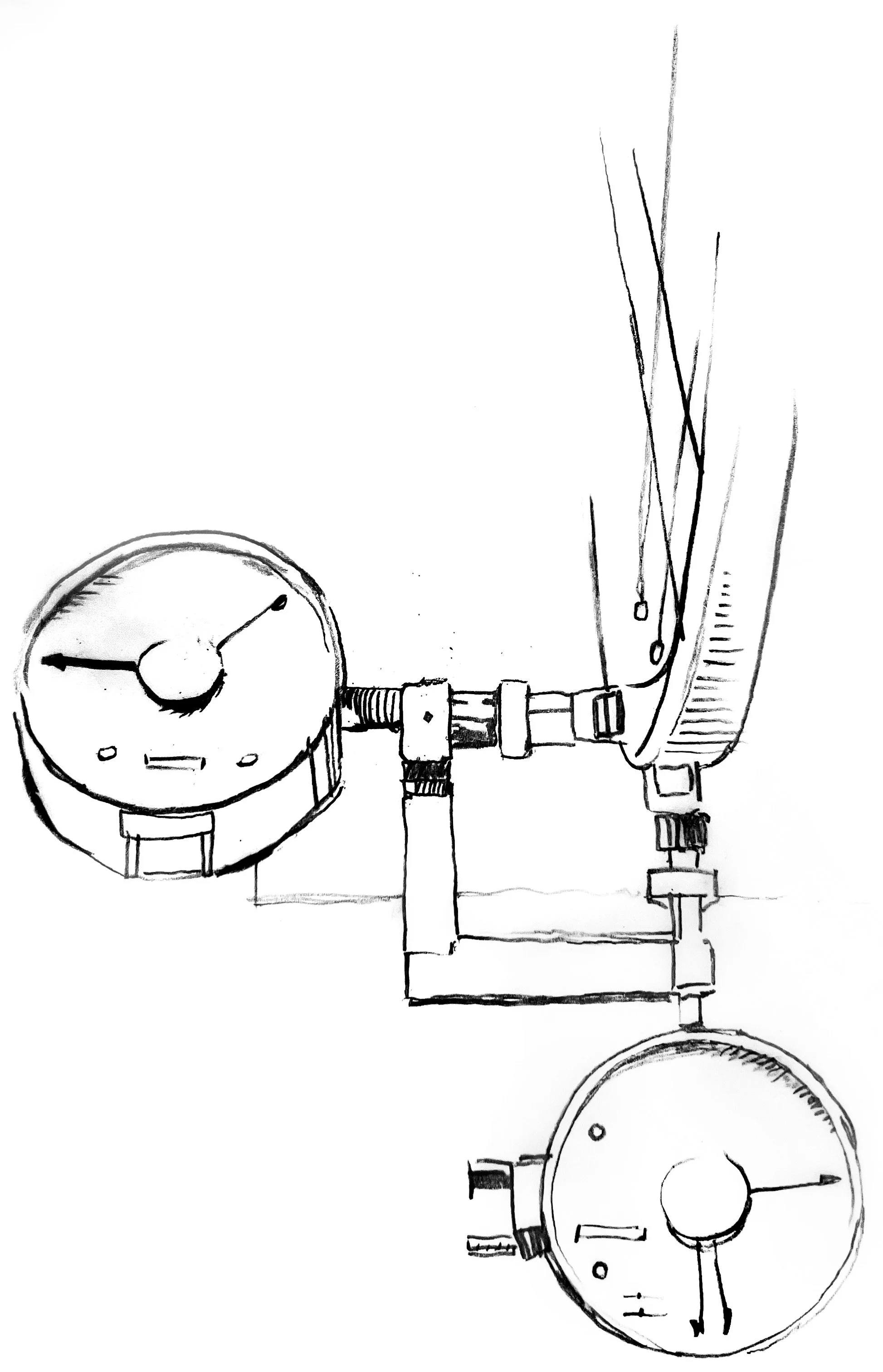

John is working with a P&K Lie 05 truing stand. It measures down to 0.05 mm, less than the thickness of a piece of paper. Astonishing accuracy. And this stand also provides both radial and lateral rim runout. The P&K Lie is a dual-dial indicator stand. So, John is getting the side wobble and up-and-down error—a nonlinear readout. What does that mean? The dials show only 160 in. of sweep (like a car speedometer). At the outside edges, they read in millimeters, but when approaching the center, accuracy skyrockets. The stand reads in increments of 0.05 mm at the center. This is crazy effective. Now John can use a dial indicator from the very beginning of a wheel build. And it’s gorgeous. The stand is aluminum with solid brass parts; all screws are made out of stainless steel. It has a three-point bearing for absolutely constant axle position, is easy to adjust for different wheel diameters, and the dial gauges are a patent design by Peter Lie. This the king of truing stands. Thoroughly beautiful, immaculate in line, elegant in form, it’s the gold standard for the sophisticated world of modern wheel building. Ultra-precise, it is as rugged as it is beautiful, and there’s a good chance it cost more than your bike. Plus, it’s more accurate than manufacturers’ wheels. This stand is used by Strada (UK), Vittoria (Italy), Lightwolf (Germany), and John Drake of Tangent Cycles.

John could give a keynote at TED on concentration.

Quiet moments pass. The silence fills in around us. Time slows down. John is tightening each spoke one full turn, starting at the valve hole and working his way around until he gets back to square one. His feel is keen and sensitive. He continues bringing up the tension slowly, one spoke at a time, one full turn at a time, until the wheel begins to firm up. Then, as the spokes become tensioned, it’s a half turn, then a quarter turn. Forty years of experience and feel are on display. The spoke wrench in John’s left hand, and a pair of special spoke pliers in his right (the pliers keep the spokes from winding up torsionally)—turn, check. Turn, check. Turn, check. And here’s the thing: each “check” means John is watching the vertical true, horizonal true, rim dish, and spoke tensioning and de-tensioning—watching, listening, recording. It’s like he’s catching every blink, every utterance. John doesn’t pay me any notice; he’s just so there. He watches the P&K Lie custom-built gauges—huge gauges, nonlinear, 100 percent dial gauges—and listens to the scraping of the truing stand’s feelers against the rim, his DT Swiss tension meter in constant use. As soon as he has the lateral truing reasonably good, he picks up a Harbor dishing gauge from Abbey Bike Tools—but wait, let me stop here for a moment. There are a lot of simple ways to dish wheels, but this tool is a standout. Machined from big billets of aluminum to a final shape, it’s a gorgeous gem, and it must be as nice to use as it is to look at. John gets a dish reading. And wait—while we’re at it, we should talk about another amazing tool John is using. It’s a box he’s using for spoke de-tensioning. This mighty box is a masterpiece in design and helps in a way that nothing else can to create wheel architecture, a wheel that stands.

Genus Americanus (seating and stress-relieving the spokes).

Rolf Dietrich, a German engineer who created the paired-spoke wheels that were under the US Postal Service team in the Tour de France, designed this box John uses for spoke de-tensioning (stress release is a huge part of making a wheel that will stand, which in turn increases strength and dimensional accuracy). “A damn clever tool,” says John. He moves back and forth between Dietrich’s box and the P&K Lie, constantly checking the tension with a DT Swiss handheld tension meter and the Harbor dishing gauge. What John does is no joke; the experience that comes from 40 years of wheel building makes his handcrafted wheels legendary.

No wheels exist in nature.

“A wheel has this kind of completely real and completely mythical anatomy. It operates on both planes. The wheel is deep. A hallmark of man’s innovation. Throughout history, most inventions have been inspired by the natural world. The idea for the pitchfork came from forked sticks, the airplane from gliding birds—but the wheel is 100 percent man’s. Evidence indicates that the wheel was invented around 3500 BC in Mesopotamia, to serve as a potter’s wheel—300 years before someone figured out how to use them for chariots. The ancient Greeks invented Western philosophy and the tuned and torqued-up chariot.”

—Smithsonian Magazine

Smiling broadly, John holds up my wheels. These wheels are conceptual, a straight trip through time. The beauty, the engineering, the artistry, the design, the science—what John has built and holds in his hands feels intimate and larger than life, mythic and at the same time a sharp visceral presence. They are just killer. I can’t wait to get them under me, far away from the sound of traffic, on a long and empty stretch of road.

Saddle up.

Tangent Cycles is as roided out as any premium shop could feasibly be, fully credentialed, with a slew of exotic tools and equipment. But honestly, what all this fails to capture is the immediacy, the absence of latency between brain and bike when you talk bikes with John. And with the absence of intrusion (it’s just you and John), this is a peak experience. In the world of attainable this is a super bike shop. The kind of experience that changes everything. Now grab your keys and get out there (John may be out riding on one of those pine-ribbed country roads in North Carolina, so you might want to call first).

Continue Reading

The Fit

Equal to a first-class seat on the bullet train, Retül is a technical tour de force...

The Frame Builders

Can legacy bicycle manufacturers ever catch up? Not likely...